In central Texas, we love our trees. They provide beauty, softness, and scale, and are the original shade structure, protecting us from the harsh sun. The sculptural limbs of live oaks and the soothing sound of a breeze through their leaves draw us to their embrace. One of our goals as architects is to foster a dialog between our buildings and their sites. When evaluating a site, we observe the prevailing breezes, sun orientation, views, and–of course–the trees. These observations are made with an eye toward creating harmony between structure and setting.

Achieving that harmony poses challenges. We want to be near trees, locating our buildings close to them and creating patios and courtyards under their canopies to take advantage of their shelter. However, what’s good for us is not necessarily good for them. Too much impervious cover deprives the roots of air and water. Too much water deprives the roots of air. Excavation for foundations and retaining walls can wound roots and stunt growth. Construction equipment can bang into trunks and limbs above and compact the soil below. These impacts can compound, placing undue stress on trees which can cause wilting or death, and cutting short that dialog between building and site.

How do we protect the health of the trees while taking advantage of the opportunities they provide?

- We consider their needs from the earliest stages of design, often working with an experienced arborist who can help us assess the viability of the trees and strategize with us throughout the project.

- We make sure the whole design team understands the priority of working with the trees. This means not only being familiar with acronyms like RPZ (root protection zone) and CRZ (critical root zone) but also understanding what design interventions can hurt or help the trees.

- We stay up to date on construction techniques and building products that facilitate construction in close proximity to trees without detriment to their root systems, and employ them to solve technical challenges.

- We adhere to established best practices during construction, such as documenting our tree protection strategies, remain available to modify solutions in the field if unexpected conditions are encountered, and include a post-construction maintenance plan and schedule in close-out documents.

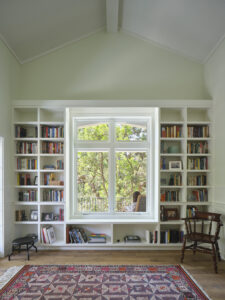

At our Ridge Oak Residence, there were magnificent heritage live oaks throughout the property. The greatest of them sat in the center of the site, wrapped on two sides by the existing house and completely paved over with a stone courtyard. We sought to wrap the tree with a third wing of a new house which seemed like a daunting risk. However, the City of Austin has a sturdy tree ordinance and knowledgeable arborists on staff. They worked with us and our arborist on a plan to remove the stone paving, aerate the roots, and bridge the foundation of the new structure over the critical root zone. That bridging led us to create a floating “ribbon” of concrete which sketches the fourth side of the entry courtyard, giving definition while resting very lightly on the earth. In essence, by respecting the Critical Root Zone of the tree, we gained a leitmotif for the design of the house.

We took careful measurement of the tree canopies and shaped our roofs to mimic the lines of the limbs. Minor tree pruning (less than 10%) at the appropriate time of year lifted the limbs slightly off the roof surfaces. That careful pruning and an early deep root feed helped the trees through the stressful months of construction. We knew that once the house was complete, the roof design would funnel runoff into the courtyard. Too much runoff, however, would saturate the ground and suffocate the root system–potentially leading to tree stress, fungi growth, or root rot–so we provided multiple area drains to release any excess water that would otherwise accumulate.

At the University of Texas at Austin, a stand of heritage live oaks along the East Mall invited us to extend an “outdoor living room” from our student center at the Jackson School of Geosciences. Here, too, we worked with an ISA Certified Arborist who penned instructions to the contractor for tree and root protection during construction. He confirmed the trees were all healthy and viable, but informed us that the soil had been compacted substantially by foot traffic over time. Our strategy was therefore to increase air and water penetration to the trees’ root systems with a goal of achieving an optimal 50-60% soil porosity. Sensitive areas were fenced off during construction, and soil repair, aeration tubes, and new irrigation were incorporated into the scope of work for the new courtyard.

To ensure the roots would receive adequate water and air, we specified a pervious paving system for the inhabited courtyard surface. As shown in the diagram below, we started at the bottom with a geotextile fabric covered with a gravel base course. Above that, a special pervious concrete pad was poured, which is strong enough to bear the weight of campus maintenance vehicles. On top of the concrete pad we added another layer of geotextile fabric, a bedding aggregate, and stone pavers with 5/16” joints filled with the bedding aggregate. Rain water goes through the bedding aggregate and is diffused through the pervious concrete to the roots below.

Support for this paving system required the addition of subsurface retaining walls and other structural components. Locating roots along the paths of the walls was a bit like an Easter egg hunt, and we were often at the site to improvise solutions when we encountered unexpected roots. Air spading was used extensively, and when roots were located they were fertilized and wrapped with damp cloths while exposed. The retaining walls were poured with passageways around the roots to accommodate future growth and create the healthiest possible environment for the trees. This approach allowed us to create a vibrant habitable space that contributes to the happiness of both the people and the trees.

Design Phases

- Consider an ISA Certified Arborist (in Texas) as part of design team or special consultant.

- Include analysis of existing tree health during site analysis and consult ISA Certified Arborist on your trees’ estimated life expectancy. There’s no point in spending heavily on a tree that looks good now but will likely be gone in 5 years (example: American Elms live average of 60 years in Texas).

- Familiarize design team with common terms:

- RPZ – Root Protection Zone

- CRZ – Critical Root Zone

- Limit disturbance in RPZ and prohibit disturbance in ½ RPZ.

- Ensure trees get air and water percolation to roots. Optimal soils are 50-60% pore space, but this has often been compromised due to foot traffic in existing spaces or construction activity in new spaces.

- Control soil compaction during new construction around existing trees.

- Undertake soil repair and aeration, then control compaction when renovating around existing trees.

- Consider ways that building near trees affects drainage patterns:

- Trees that are not used to getting a lot of water will drown if swamped by building drainage.

- Trees cut off from drainage it used to have will experience stress and possible decline. Curb cuts, rain gardens, diversion swales are great tools used by designers.

- Consider how altering the microclimate around a tree will benefit or harm soil biology (example: building on south side of tree reduces light around tree and will alter the number and type of invertebrates and microorganisms in the soil).

- Understand future growth habits of root system.

- Limit canopy disturbance and prohibit removal of more than 30% of canopy

- Consider space requirements of construction access in terms of canopy disturbance.

- Understand future growth habits of canopy:

- Account for future growth of young established trees

- Plan building massing that works with established canopies of mature trees

- Ensure trees get light and air to leaves (example – do not plant new trees too close to existing trees).

Bidding / Contractor Obligations

- Remind Contractor that tree protection is delineated in the Contract Documents.

- Confirm that Contractor is aware that monetary consequences of tree damage are written into Specifications:

- All damage to trees determined by ISA Certified Arborist.

- Minor damage to trees or unusually high levels of stress resulting from construction activities require remediation as recommended by ISA Certified Arborist and implemented at Contractor’s expense.

- Significant damage resulting in compromise of overall health, form, and structure will result in Contractor replacement of tree with one of equal quality, size, and value, including costs associated with maintenance program and maintenance to monitor tree health for period of one year after replacement or, reimbursement to the Owner for the value of the tree as determined in the Tree Protection Plan.

Pre-Construction

- Obtain ISA Certified Arborist recommendations for pruning and fertilization prior to construction.

- Undertake limb remediation.

- Remove dead limbs

- Properly trim limbs that may conflict with construction access

- Raise low limbs temporarily using ropes as an alternative to trimming

- Perform deep root fertilization to ameliorate stress caused by construction activity.

- Develop pruning and fertilization plan addressing tree maintenance for the duration of project construction.

Construction Administration

- Keep tree protection in place for duration of construction per Tree Protection Plan (architect should inspect regularly).

- Prohibit contact of construction equipment and materials with trees (including roots).

- Provide temporary irrigation for duration of construction. Consult ISA Certified Arborist for watering schedule as watering is effected by many factors – soil type and bulk density, weather conditions, time of year, etc.

- Route utility lines around RPZs if possible. If not, use air spade to remove soil for utility routing, bore under roots at minimum depth of 4’ to route under roots, or hand dig for utility routing to preserve 1” and larger roots.

- Cover exposed roots with soil within 8 hours. If this is not possible, cover roots with hardwood mulch or wet burlap to prevent drying out.

- Restrict grading within RPZ to only occur in the areas indicated in Contract Documents and be done by hand.

- Grading outside of RPZ but within Drip Line should proceed with caution. Roots encountered 1” or greater to be hand cut with clean sharp tools at the limit of grading.

- Do not alter soil pH (acidity or alkalinity) in or near RPZ.

- Locate stucco mixing and concrete washout away from Drip Line to eliminate contamination.

- Do not allow soil stabilization with lime or related products within 10’ of RPZ.

- Consult ISA Certified Arborist for species specific protection (example: Oak Wilt protection in Central Texas).

Post-Construction / Owner O&M

- Obtain ISA Certified Arborist recommendations for fertilization after construction.

- Develop a post construction maintenance plan and include schedule in close-out documents.

- Adhere to the maintenance plan. The end of the Project does not mean the end of tree care. Large trees often take 3-10 years to adapt or show decline from construction stress.

If you or your organization would like more information on this topic, please email us.